On the streets of Garibaldi in Tunis, in a male dominated neighbourhood, stands a fierce monument to- a tender war.

One that celebrates the fire of our own bodies, (hurts no one) and is a public altar to female rage and self love in all its manifestations.

It inhales inward, in air: “Be tender with yourself,

حن على روحك

breathes outward, in spitfire: “Listen to your rage”

اسمع غلك

The walls of Tunis are large and tall facades – like fortresses. But open a door and find yourself in an interior, hidden, universe of hand painted courtyards filled with intricate details- almost a metaphor for how social life is segregated in these streets. Outside boulevards are lined with cafes occupied entirely by men. Travel further into the heart of the city and winding alleyways reveal hidden interiors- a city embedded within: in underground bars, erotic libraries, in intimate meeting spaces created by women, people come together to embrace their inner intricacies, complexity and difference.

Tunisia’s 2011 ‘Jasmine Revolution’ launched an explosion of public political dissent unprecedented under the culture of fear and silence imposed by generations of dictatorship. What began in fire and rage, when street vendor Mohamed Bouazizi set his own body on fire in protest, blossomed into an inextinguishable desire for change; old structures burnt to the ground and new conversations began in the streets about what would replace them, and whether they would affirm feminist realities.

Prior to 2011, already established women’s groups were active in ‘state-sponsored feminism’ under the dictatorship. After the Revolution, other feminist groups, including our partner CHOUF, started to emerge. These groups were composed of LGBTQ people and of women from different political backgrounds, many of whom had been part of illegal political parties and alternative cultural scenes repressed under the dictatorship. The diversity represented in their lives, voices, and aims marks the broadening of the feminist movement in Tunisia. For many of these activists, the Revolution marked but a turning point in their ongoing struggle to build a society in which all can flourish,

Prior to 2011, already established women’s groups were active in ‘state-sponsored feminism’ under the dictatorship. After the Revolution, other feminist groups, including our partner CHOUF, started to emerge. These groups were composed of LGBTQ people and of women from different political backgrounds, many of whom had been part of illegal political parties and alternative cultural scenes repressed under the dictatorship. The diversity represented in their lives, voices, and aims marks the broadening of the feminist movement in Tunisia. For many of these activists, the Revolution marked but a turning point in their ongoing struggle to build a society in which all can flourish,

Within this context, rage has played a significant role in social transformation and feminist organizing in Tunis, for it was rage at injustice, at unquestioned privilege, at the status quo, at violence and inequality that carried thousands to the streets. Like every emotion, rage carries knowledge; it helps us understand what feels right to us, an internal compass pointing us towards knowing what we (don’t) want. Yet, rage is not an emotion we want to feel forever. As activists constantly feeling like we need to fight, we can easily become trapped in cycles of rage, burning ourselves out.

In an intimate ritual, we gathered together with a group of feminist and LGBTQ activists in a hidden courtyard inside the belly of a 16th century souk to share our stories. We used fire to represent the rage each of us carry inside of our bodies.

In our ritual of rage, each woman sat before a line of fire, struck a match and answered the question: “What is the source of your rage?”

One by one, each woman spoke about her experience of the emotion- self directed rage, rage at the hands of an abuser, rage at other women, rage at social and political injustice, anger that lived in memories and in deep-seeded wounds:

The source of my rage is a lack of recognition.

I’ve never let my rage in- I come from a family of volcanos so, I always had to be the one who calmed

I deny rage. It accumulates inside me. But when it is released, I turn the dagger inwards.

My rage is a mountain, covering all the landscape; the source is beyond its ridges.

The source of my rage is my troubled relationship with my abusive father.

The childhood I never had.

I am angry at everything. (all of the time) and yet.

In the second part of the ritual, each woman blew out her fire and spoke about the things that make her rage become tender, as an articulation and reminder that the world we want to live in is – softer than fire. As each woman spoke of what softens her rage, the contents of the worlds we hope to collectively create began to take shape: world defined by love, understanding, mutual support, respect, self-knowledge, and undefined/unrefined beauty:

I go tender when I decide to live for myself; not live for anyone else.

kisses make me tender

I go tender when someone tries to understand why I am angry

I go tender when I wake up in the morning and see my daughter next to me; I look at her and I’m filled with all the tenderness in the world.

I do not go tender; my rage grows cold. I cannot feel tenderness.

I go tender when I recognize that there’s too much beauty,

I don’t want to be

Burning.

While we spoke of tenderness, many reminded us of the ways tenderness has been forced on women- when and how we allow our rage to become tender is a choice we must make for ourselves.

The Tunisian dinar carries an image of a woman offering an olive branch of peace outwards to an invisible, imagined other (or, maybe, out towards the whole world). Too often women are expected to be the bearers of peace, offering our tenderness outwards. Yet we are rarely (if ever) taught to offer the same inwards.

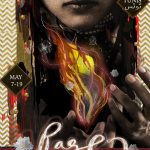

The image emerged of two women gazing forward, fiercely. In one hand each woman holds her fire close to her body, illuminating what rests inside- her embodied emotions, internalized experiences, desires- while their other hands intimately embrace each other in an act of support and solidarity, a jasmine plant rising between their outstretched arms like smoke.

On a particularly male dominated street, women from across different backgrounds, ages, beliefs systems, sexualities and genders came together to paint their bodies on the walls for all to see, in a celebration of unbound self-expression in public space.

On a particularly male dominated street, women from across different backgrounds, ages, beliefs systems, sexualities and genders came together to paint their bodies on the walls for all to see, in a celebration of unbound self-expression in public space.

In Tunisian, صرم refers to a woman’s ()

Used as an insult, by men, profanity, site of shame- how then are women supposed to refer to their tenderest parts?

Next to a bar that prohibits women, feminist activists climbed scaffolding, danced, and held space for conversations with observers and passer-byes as they painted self-interpretations of their most intimate parts into the mural. A radical act, bringing our privates into public space without fear or shame.

Collaborators (including calligrapher Mohamed B. Dhia and poet Syrine Chekili) joined us along the way, offering and weaving their beauty into the image. Secret poems in Arabic calligraphy adorn the wall: a fire gently whispers “this is the rage of women who stand side by side, glowing soft and tender,” and the shadow of the women’s bodies tell us of skin on skin:

الجلد عالجلد نارحبار فايضالجلدعالجلدسطرقبربحرمهبولمبلولمزطولخايضالجلدعالجلدكلاموملاموسلامونفسعفسوحبسعارقالجلدعالجلد…والجلدغارق.

As we painted into the first days of Ramadan, streets became empty, but conversations continued. At dusk, we gathered together on the last night of our mural- Gathering chairs and tables from close cafe’s, gathering flame coloured bouganvillae off trees by the pavement. Gathering all the memories of red that the week contained. As we heard a final call to prayer that evening, 20 women gathered at a fearless feast, carrying bowls of dates, fig and chillies to an iftar dinner on the streets. We each lit a flame at the base of the mural, and wrote our own stories of rage and tenderness within it’s folds.

We will not make monuments to our wars, we will make magic of our wounds, celebrate our bodies, show ourselves tenderness and never doubt the rage that protects the things we love. Two women hold flames in their open hands, Their other hands embrace each other, a jasmine plant rising between them like smoke.

One women reminds us:

حن على روحك

“Be tender with yourself”

As the other tells us:

إسمع غلك

“And listen to your rage”

__________________________

This Fearless Collective mural in collaboration with CHOUF stands as the first feminist monument in Tunisia.

Will this fire ever stop burning?

زعمة النار تطفاشي؟