On W̱SÁNEĆ and LEKWUNGEN territories, Indigenous women from across Turtle Island and women with roots around the world came together to spread their stories like a salve over our wounded relationships with the earth, ourselves, and each other. Between plant, story, and salt water, we became each other’s medicine.

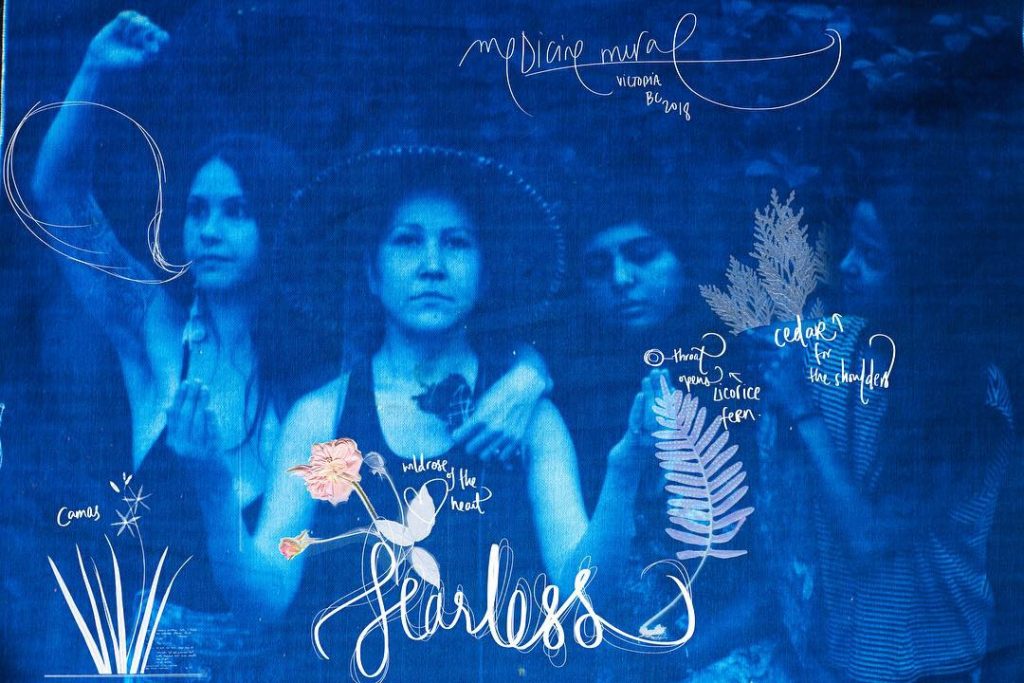

On Esquimalt Road, four women stand side by side as each gazes towards her path

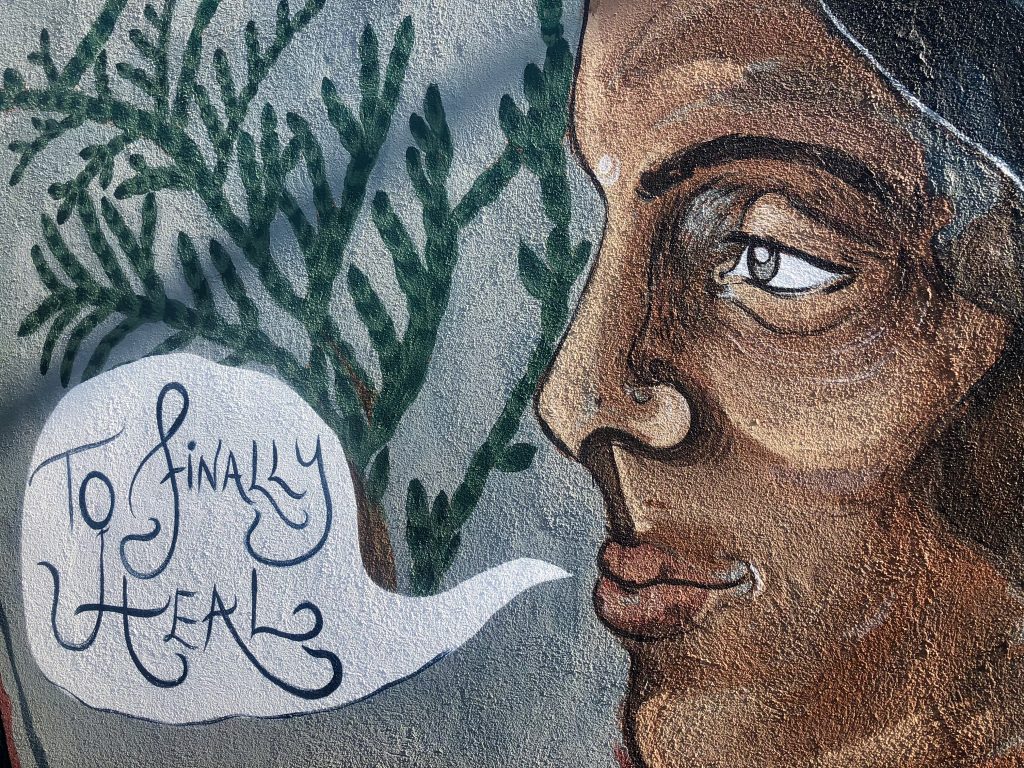

To finally heal.

ȽÁU,NOṈET

The sun rises over the ocean in SȾÁUTW̱ warming the sky in shades of orange and rose as we immerse ourselves in the water, once, twice, four times. Bathed with salt water and cedar, morning light, and sacred intentions, we cleanse ourselves in a ceremony led by a Coast Salish woman who has invited us to visit her home lands and share her waters, her stories, and the practices she has collected on her journey, to heal.

As she tells us the story of the land, she honours the lands and waters to which she is linked, her cultural practices, her ancestors and her family- those who are present today, those who have passed, and those who are yet to arrive. In doing so, she is honoured as well, for she is the descendent of the futures her ancestors imagined- through lineages of resilience, she is the embodiment of their intentions and resistances. “We are Salt Water people- our ancestors emerged from Salt Water and came to live with these territories.” She talks also of settler occupation and the open wounds it has left on the lands, bodies, and spirits of Indigenous people across Turtle Island: “it hurts that I have to tell you where this hurts by using words that aren’t from my language.” Victoria, the name of a queen that did not know this soil. British Columbia, this was never your land.

Recite instead: LKWUNGEN- the place to smoke herring, W̱JOȽEȽP- the place of maple leaves,

sxʷiméɫəɫ – the place of gradually shoaling water

Remember instead:

W̱SÁNEĆ- the rising up people

These names carry stories: spoken geographies that bond Indigenous nations to their territories through kindred relationships to the lands and waters, plant and animal nations, skies and Creator beings they have lived with in sacred harmony since time immemorial.

On these unceded Coast Salish territories, Fearless Collective joined the Saltwater People and Indigenous women from across Turtle Island to examine our wounds and gather our remedies in a collective exploration of medicine.

When the first colonizers washed ashore W̱SÁNEĆ and LEKWUNGEN beaches- lost, sick and sea battered- they were met by thriving Indigenous nations intimately connected to their home territories, who offered ‘the hungry people’ food and medicine- following their cultural protocol to care for those who are unwell. Once recovered, those first uninvited visitors found that healthy and strong Indigenous people proved threat to their newfound dream of settling the abundant lands they had accidentally stumbled upon.

And so, treaty bearing traders, ‘civilizing’ missionaries, and convoys of men offering false promises and blankets laced with smallpox were quick to arrive to undermine Indigenous nationhood. And they saw that unlike their own people, women of these nations held positions of leadership, were respected as carriers of knowledge, had agency; they embodied kinship ties to land, water, community and held the power to (re)Create their nations. For many of these nations land itself, through which all life is sustained, was associated with feminine power.

How does one extract natural resources from lands and waters when the people they belong to treat them as kin endowed with spirit and respected feminine energy?

At the root of the current crisis of murdered and missing Indigenous woman and girls across Canada is the dehumanization of Indigenous women by which this country was founded. Yet, in spite of the ongoing efforts to force Indigenous nations to disappear, Indigenous women continue to practice their traditions, speak their languages, and live their stories with the resilience to be Indigenous and self-determining without limitation.

In an intimate Ritual Indigenous women from nations across Turtle Island and settler women of mixed ancestry gathered together to articulate our wounds and vision our decolonial paths towards healing.

Indigenous women and women who have migrated to Turtle Island have been historically pitted against each other: many of us were taught to believe that our safety and survival depended on the rejection of the other. We have been separated, divided, made to feel that our struggles are ours alone. And in our isolation we have been made to feel powerless. In this context, gathering together to listen to each other’s stories became both a radical act of refusal and an opportunity to discover what we share.

Under the arches of an apple tree, we were welcomed by the Elliot family into a garden in the Tsartlip First Nation on W̱SÁNEĆ territories, we answered the question: What are your roots? Created, undone, scattered, dispossessed and settled, we discovered that while each of us arrived on these territories by very different routes, all of our journeys have been affected by British colonialism- whether through settler occupation, displacement, genocide, the drawing of borders, indentured labour or slavery, each of us carry a piece of empire logged in our histories.

Having dug into her grounding, each woman then sat before a mortar and pestle made of wood and stone, surrounded by a pharmacy of medicinal herbs, sacred plants, and roses. One by one we chose our medicines and crushed them while answering the question:

Can you show me where it hurts?

“It hurts that I have to tell you where this hurts by using words that aren’t from my language. It hurts that this is probably the very first time that I’ve been with a lot of women of color.”

(add cedar, add sage)

“My shoulders hurt because of what I carry everyday- the displacement, the loss; I feel pain in my hips because of the ways I have felt invisible and rendered the women in my life invisible; My throat hurts because of the silences I impose on myself, because of the things

I

do

not

say”;

(mix rosebuds- and crush)

“I feel sick to my stomach because the violence against my people never ends, I see white people who benefit from this violence – happier than I am.”

(grind into dust- make a salve)

“My jaw hurts from all the anger it has to hold back. I come from a lineage of women who don’t pay attention to where it hurts;

It hurts all over;

It hurts in my womb because of the violence that has been played out on my body. My body is my first battleground.

It hurts in my feet because I long for a sense of place and belonging;

My spine is hurting to remind me that it’s there.”

But for every poison, there is an antidote.

In many traditional medicinal practices, poisons could often be alchemized into medicine. While it is important to identify the wound, it is (more) important to know what heals it. Our justice systems are built for punishment- not for prevention, regeneration and deep repair.

“The remedy is finding softness. The remedy is being brave. The remedy is finding magic. The remedy is having hope. That I will find who and what I need. The remedy is that I will always love my children. I will never abandon them. They will never have to live without answers.”

The remedy is:

“Trusting myself and the people around me, feeling that I don’t have to be alone all the time; Knowing that I can rely on something that is greater than me/ looking for signs

Going home, feeling the sun all over me, feeling dried salt water on my skin for days and in my hair, being in all elements of my territory: in the ocean, on the beach clam digging, in the forest, being with my community, little ones and old ones;

Remembering my grandmother, and knowing that these bones come from her bones come from her bones and so there is power and history and story in my bones and in my children’s bones;

Fully surrendering, reaching out and asking for help;

True and unconditional love;

Solitude;

When I remedy myself, sometimes I wound others; acknowledging and owning it, talking to others who are the inheritors of privileges that come at the expense of other, always making space and holding space;

Laughter;

Not feeling guilt where I find remedy, my white mother is my source of healing;

This: my remedy is knowing that there are spaces for these conversations and that we can create spaces for these conversations.”

As each woman located her wounds in her body and her history and articulated her remedies, we began to imagine the body as a map, collectively crafting a vision of women’s bodies as their own sovereign territories.

What would happen if we treated the health of the physical and social spaces we inhabit with the same attention as we treat our own bodies? What would happen if we looked at our own bodies the way we do the natural landscapes that leave us awestruck, in all of their imperfection and completeness?

The image of four women, each representing an archetype of healing, emerged:

One woman drapes another in cloth, representing the feminine soothing presence of generations of women who have helped others deal with trauma over the centuries, showing us the healing force of Community.

One woman drapes another in cloth, representing the feminine soothing presence of generations of women who have helped others deal with trauma over the centuries, showing us the healing force of Community.

(make an unceded map of the body)

The woman being draped stays with her Grief, acknowledging its presence and letting it serve its purpose.

(I touch my temples, my heart, my shoulders, my womb)

One woman holds her hands up, open palmed towards the sky, in a Coast Salish gesture of gratitude and welcome, remembering her culturally-rooted Traditions, practices which treated healing as integral to living: written in our cultures is a codex of recitations, rituals, ceremonies and spirits that can bring us closer to being whole.

(mark all cardinal directions on my skin)

Another woman stands tall, dressed in light, fist held high, representing Resistance and power: resistance not only within the context of our movements for justice, but also the power we need for our own personal journeys, the discernment we need to know when it is time to no longer let grief into our houses, to pick ourselves up, and begin again.

At a corner on Esquimalt Road, on SXIMEȽEȽ territories, we began to collectively paint a monument to our stories of healing and resilience.

For each of the wounds women articulated Indigenous women engaged in reclaiming and revitalizing their land-based cultures prescribed a Coast Salish plant medicine:

A wild rose bursts out of the heart, a universal symbol of love, used to ward of bad energy it is soft petalled, but armed with thorns; just like the heart, it knows how to protect itself. It is tender and strong in the same breath.

A licorice fern climbs up the spine towards the throat to help clear it, allowing us to use our voices.

A cedar branch rests on a shoulder ready to brush away any negativity that might weigh us down, letting us stand tall as we face the world.

Camas flowers sit next to the stomach to nourish us as we walk our paths.

W̱SÁNEĆ artist Chas Eliott then prescribed a story for every wounded body part to help us activate those plant medicines:

An eagle, who is always attuned to itself, rests in the gut, representing intuition and timing, reminding us to listen to our instincts.

A wolf rests on the shoulder reminding us to be strong and resilient through the good and the bad, symbolizing balance and protection.

A bluejay and an orca are intertwined in the heart: while the orca represents family and the things that matter, the bluejay is chia, or “hard working woman.” In W̱SÁNEĆ mythology:

Two frogs face each other inside of a spindle whorl in the throat:

“It seems like every culture has one of those spindle whorls in their culture, and so I used that to tie us all together. And the circle itself means so many different things, but one of them is it’s whole, it’s everybody. Also, there is no beginning, no end to it. In the circle there’s a frog design. Where I’m from, W̱SÁNEĆ, the frog is known as an announcer, a messenger of change, and so signifies change. When the great flood came here, the first to emerge and let us know that the waters are starting to recede were the frogs; we were notified by them that things are changing now. They also tell us about the coming of spring: the frogs all start to croak, so when it’s winter time, when we’re having our winter ceremonies, once we hear the frogs start croaking we know it’s time to stop our winter ceremonies and the coming of spring is happening. So the frog is really like a voice, it gives a voice of change. New beginnings. New things to come.”

Around the world, colonial regimes tried to divide communities to conquer them, casting apart kith and kin and crafting inter-community conflict. Gatherings and ceremonies intended to celebrate and renew relationships were banned. On these territories, potlatch feasting ceremonies were outlawed. Many went into hiding, nurturing secret spaces to keep their traditions alive.

To honour those traditions, in defiance of those who want to keep us apart and in celebration of each other, we feasted in the streets together, creating a safe and Fearless space where we could dance by the railroad tracks, invoke languages that our ancestors were forced to forget, and support each other.

We witnessed our stories reflected in each others over and over and over again. And discovered:

We have been thirsty for each other.

While feasting together was outlawed in one part of the world, the very salt used to cook our meals and nourish our bodies was being taxed by the same regime in another.

In an ode to a decolonial movement of the past, which used gathering salt from water as a radical act of protest against, we performed our own Salt Water march.

Water, stories, the body- all are mediums, for travelling into and through this world.

Along the rocky coastline, each of us evoked an ancestral spirit to acknowledge our journeys and place ourselves in a larger web of relationships. Linked together by a cloth soaked in salt, we walked from the ocean to our wall to honour our stories of resilience, the salt water in our bodies, and the Salt Water nations who invited us to come together in their territories.

In our time together, we experienced decolonization and Indigenous resurgence as being two sides of the same coin: as one system crumbles, each of us are responsible for visioning and affirming the futures we want to create and inhabit. In this time of turning tides, we are remembering, making, and remaking who we are and our relationships- to our surroundings, our selves, and each other. Which of our traditions support our collective flourishing? Which ones no longer serve us? What do we choose to honour?

Every person who walks past the wall gives us a gift- sometimes a dance, a bundle of sage, other times a life lesson.

Indigenous Activist Rose Heny offers a song of indigenous protest:

Indigenous Activist Rose Heny offers a song of indigenous protest:

“The elders say that cedar gives you power. And as you see up there, in the (mural) painting, this woman up there, that’s where power is, because as Matriarchs, the power lies within every woman. So this song that I’m going to give you, it’s a song that I’ve carried for 32 years as I’ve been walking for the missing and murdered Indigenous women. Because we are the life givers and we’re the first teachers to the next generation and so when we have our drum playing- the first noise that every person hears, is their mother’s heartbeat.”

Antony, a Coast Salish storyteller, tells us: “the Creator gave the people a plant to cure their grief”

When the colonizers first came to this land, they saw this strange red crowned bush endowed with protective spikes and thought it was a nuisance. They called it the Devil’s Club.

For the Indigenous people of these lands, the plant was no devil in disguise, but a blessing ‘most scared’- an abundant source of healing medicines for a vast range of illnesses. Yet, this is a plant that demands attention- it’s practice of growing in dense thorny thickets forces one to slow down and tread its territories with care.

In Coast Salish art, this plant is depicted as steps, with stages to be climbed. Standing in the streets on our ladders, side by side, through salt streaked eyes we began our ascent. Together, we adorned our wall with medicines made of sacred plants and stories, visits with our ancestors, a sense of belonging and community, moon gazing, good food, good love, and all that heals, body and soul.

Through collectively creating a monument to our remedies for healing ourselves and the spaces we inhabit, we became- each other’s medicine.

Through collectively creating a monument to our remedies for healing ourselves and the spaces we inhabit, we became- each other’s medicine.

When you name something you allow the possibility for it to exist.

In SENĆOŦEN, the word ȽÁU,NOṈET teaches us that there is a way to finally heal.

We offer our deepest and most sincere gratitude to the Indigenous nations on whose territories this work took place: the Lekwungen (Chekonein, Chilcowitch, Swengwhung, Kosampsom, Whyomilth, Teechanitse, Kakyaakan, Songhees, and Esquimalt) and W̱SÁNEĆ (SȾÁUTW/Tsawout, W̱JOȽEȽP/Tsartlip, BOḰEĆEN/Pauquachin, WSIḴEM/Tseycum) Peoples, who invited us to share space and stories, on their home lands and waters. Thank you.

We offer our deepest and most sincere gratitude to the Indigenous nations on whose territories this work took place: the Lekwungen (Chekonein, Chilcowitch, Swengwhung, Kosampsom, Whyomilth, Teechanitse, Kakyaakan, Songhees, and Esquimalt) and W̱SÁNEĆ (SȾÁUTW/Tsawout, W̱JOȽEȽP/Tsartlip, BOḰEĆEN/Pauquachin, WSIḴEM/Tseycum) Peoples, who invited us to share space and stories, on their home lands and waters. Thank you.

To everyone who joined us in creating this medicine wall, thank you for knowing (loving) remembering your land, the plants that root into its soil, the spirits that protect us in the sky. Thank you for your salt water, thank you for your stories and all that fearless loving.

HÍSW̱ ḴE SIÁM, thank you respected ones, to Tomosen, Myrna, and Beagnka Elliott for inviting us to share your space.

Special thanks to Chas Elliott, Tiffany Joseph, and Farheen Haq for all of the sweet medicine, insight and beauty you shared with us.

Finally, all our gratitude to the Innovative Young Indigenous Leaders Symposium: Gina Mowatt, Nicole Neidhardt, Mandeep Kaur Mucina, Morgan Mowatt- you were the beating hearts of this work.

: Shilo Shiv Suleman Artwork: Heather Stewart, Nicole Neidhardt and Chas Elliott

Photography & Film: Jenny Jacklin Stratton

Writing: Josephine Simone

Production: Cassie Denbow